Land registries are a key trust mechanism in the real estate industry. They can only benefit from decentralised technologies such as blockchains.

Trust is the cornerstone of any kind of transaction. If one person wants to buy something from another, both must be able to trust that their respective intentions are sincere — or at least have confidence in the truthfulness of the information at hand.

If I suspect a fruit vendor at the weekly market is trying to rip me off, I’ll probably buy from the guy next door. If I have doubts about whether the mango he’s selling me was actually grown regionally and organically in Brandenburg as advertised, in all likelihood I won’t buy it — especially if it looks more like a disfigured pear.

The same applies to buying real estate. If a property is to change hands, if a plot of land is to be built on or structurally altered in some way, then ultimately a lot of trust is needed in the veracity of the information on which the deal is based.

Without that, no deal.

The land register: from medieval Cologne to today

The land register was invented for precisely this purpose. As an inventory in the form of an official register, it documents all transactions of undeveloped and developed properties, past and present. It is a “single point of truth” that is officially recorded and notarised. With every relevant legal transaction, such as purchase, inheritance or donation, it is amended; it enjoys what is known in the German legal system as “public credence”. Only someone who is registered in the land register is officially the owner, which shows you why it is so imoprtant when buying a property.

Because land ownership involves interests worth protecting, not just anyone can look at a land register out of sheer curiosity. In order to inspect the current status of the land register or to retrieve information, one must have a “legitimate interest”. In Germany, land registry offices are situated at district courts, each responsible for registries in their respective district (except in Baden-Württemberg, because why not?).

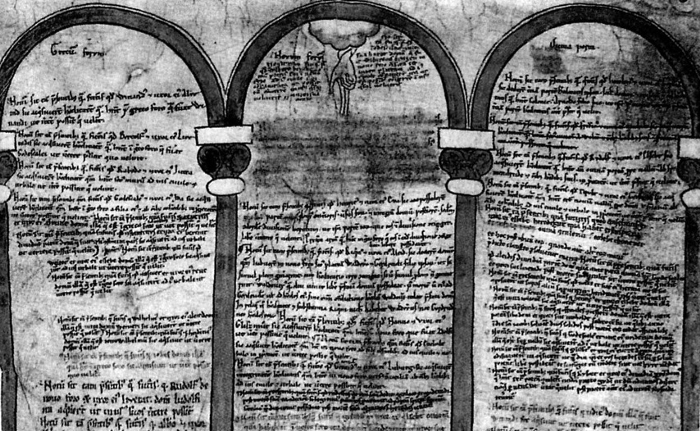

The importance of having a place where such information is stored was already known in medieval Cologne. From 1130 onwards, all property transactions in the old town parish of St. Lauritz were recorded in the “Schreinsbücher”. In the centuries that followed, numerous cities from Ulm to Hamburg followed suit. The land register as we know it today has been around longer than the German Civil Code, namely since 1872.

Cover page of a Cologne Schreinskarte, c. 1300 (Source: Wikimedia, Public domain)

What does the land registry actually contain?

So much for the history lesson. Let’s look at what’s inside. Today, a land register sheet consists of three sections:

-

Section I contains the owner of the property — or in the case of an owners’ association all owners and their respective shares. In residential and part-ownership land registers as well as in heritable building right land registers, the holder of the heritable building rights, the property owner or part-owner is documented here. In addition, how ownership was acquired is recorded, e.g. a notarial conveyance between the old and new owner, an inheritance or a foreclosure.

-

Section II of the land register sheet contains all encumbrances and restrictions of a property, such as residential rights, rights of use, usufructuary rights, pre-emptive rights, heritable building rights, priority notices of conveyance, as well as notices of insolvency, executors’ notices and foreclosure notices.

-

In Section III, mortgages, land charges and annuity debts are noted as well as their amount at the time of registration. In addition, prior notices and amendments as well as objections are also listed here.

Too little, too slow: the digital land register

Way back in the early nineties, it was decided that the land register needed to be digitised, namely in the form of the "EDP land register". So far, some electronic land registers have indeed been implemented, but for authorities and courts there is as yet no central point of information from which they can retrieve documents quickly and securely. The aim of the electronic land register is to replace the conventional paper form and to enable notaries and credit institutions to access property data online. This should speed up many things, from actually entering something into the land register to the notarisation of contracts, financing or the start of construction.

However, this does not go far enough for a modernisation project of the twenty-twenties - not in the least. In Germany's federal system, each federal state is still responsible for its own land register and uses its own applications and portals to provide notaries, owners and lawyers with access. Not much seems to have changed since the go-ahead almost thirty years ago, at least from a user interface point of view – although it might still be compatible with Netscape browsers (but not with Google Chrome, according to the homepage of the land register system in Schleswig-Holstein):

Search mask of the digital land register of Schleswig-Holstein (Source: grundbuch-sh.de.

It is worth noting that although the metadata of many land registers have already been digitised, they are still issued as PDF files for inspection. Many regions therefore additionally keep paper-based land registers. Such redundancy reduces the usefulness of a digital system, weakens data quality and leads to lengthy verification processes and data reconciliation. Although land register entries can be downloaded in an XML format specified by the authorities (X-Justice), they are not necessarily semantically compatible with standards commonly used in the real estate industry such as OpenImmo or RESO.

Due to the public sector's tendency towards secrecy, the systems lack well-documented, interoperable interfaces, which further complicates cooperation between authorities, property owners, notaries and buyers and other parties involved in the process.

Land register cost overview

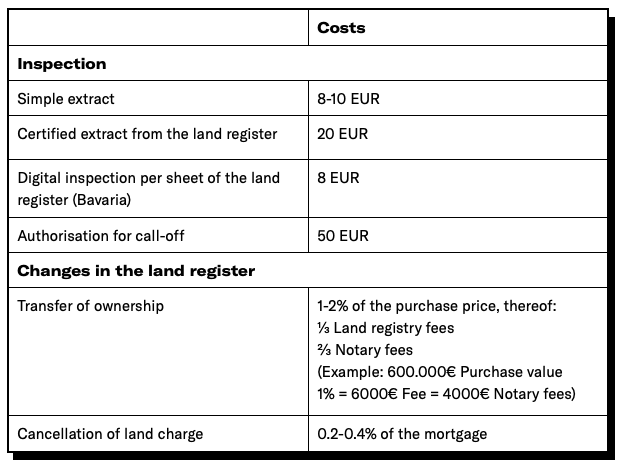

In addition to the inconsistent digitisation and the lack of foresight for a sustainable and interoperable real estate industry, the land register is also associated with considerable costs.

The “first” entry in the land register is always made when a property is purchased, or more precisely: as soon as a purchase agreement has been notarised. A notary initially makes a priority notice of conveyance in the land register. After the purchase price and the property transfer tax have been paid by the buyer, the tax office issues a clearance certificate. With this certificate, the notary applies for the entry in the land register. This process can take several weeks. Only with the entry in the land register is the purchase completed and ownership is transferred to the new owner.

In addition, an entry must be made in the land register if crucial property data changes (e.g. when the property is split), if property is transferred as part of a gift or inheritance, if there is a change of creditor or financing partner or if a land charge is to be cancelled.

The costs for changes to the land register entry generally depend on the statutory scale of fees for notary and land register costs, the structure of the legal transaction behind it, individual additional expenses of the notary and, in individual cases, the value affected in each case (purchase price, amount of the land charge, value of the right of residence, etc.). The prices vary from federal state to federal state, not only for amendments, but even for basic or certified access.

These are the approximate costs for interaction with German land registers:

The blockchain land register: more security, transparency and interoperability

Digitising paper-based processes may have been considered innovation ten years ago. Today, we should be innovating the processes themselves — through intelligent automation, secure public access and connectivity to new services, the cloud and apps.

The next step for the “EDP land register” must be a future-proof, digitised real estate industry that is open, flexible and interoperable instead of cementing isolated solutions. Blockchain technology can provide the technological basis for a solution that goes far beyond merely covering the basic functionality a land register provides.

The advantages here would not only be that the technology itself is virtually tamper-proof, but an increase in transparency, better interoperability and smoother integrability. Additionally, a blockchain-based land register could improve process efficiency in the real estate industry by enabling different actors to interact based on uniform, commonly shared information.

Anyone who wants to sell a house today relies on the cooperation of the land registry, building regulations office and cadastral office, from which different information is required. Roughly speaking, a traditional sale proceeds as follows:

- The buyer checks the land register to make sure that the desired property actually belongs to the seller and finds out about the debts and encumbrances of the property.

- The buyer and seller sign a contract on the sale of the property and have it notarised by a notary.

- After signing, the notary records a priority notice of the planned change of ownership in the land register.

- The buyer transfers the property transfer tax to the tax office and the purchase price to the notary’s account.

- The notary makes the transfer in the land register and forwards the purchase price to the seller.

With the help of digital identities, smart contracts and machine-verifiable land register entries, processing a purchase transaction can instead be mapped as a series of blockchain transactions. As soon as the relevant information from land registers is accessible to contracts, they can take over many of the tasks of trustees, notaries and offices. Service providers and credit institutions along the process chain can be notified of progress and verify data requiring protection that smart contracts themselves cannot see in plain text.

Roughly outlined, a process supported by blockchains could look like this:

- All parties identify themselves to a smart contract with their digital, self-sovereign identities, based on which special blockchain accounts are created. The necessary requirements for establishing identity and the corresponding KYC and AML requirements can already be covered by the principles of state-certified SSI identities. Smart contracts only interact with accounts that fulfil the corresponding requirements. For this purpose, so-called security or restricted tokens (EIP-1411 / EIP-1404) as well as proxy accounts (ERC-725) have been technically specified.

- The seller initiates the purchase contract with the help of the smart contract. The latter checks whether he is entitled to do so according to the present land register situation and informs other participants about the opening of the procedure by means of events.

- Other participating accounts, e.g. credit institutions and notaries, check the legality offchain if necessary and release the transaction successively through further transactions with the smart contract.

- The buyer transfers, for example, with the help of his bank, the purchase price as well as protocol fees, validation fees for the parties involved in the procedure and applicable land transfer taxes to the smart contract.

- After final confirmation, the contract updates the land register entry and finalises the transfer of ownership.

Since a full-scale introduction of such a procedure in a federally fragmented and highly regulated system is difficult to implement in a big bang, it would also be conceivable to gradually introduce it. For example, most validations could continue to take place offchain and only be stored onchain for faster information transfer and in the event of a final transfer of ownership.

With the publication of the federal government’s blockchain strategy in 2019, the government already recognised the importance of identifying appropriate applications for blockchain in different areas. There, the federal government describes the land register as an already functioning administrative process and does not consider its implementation on a blockchain basis to be sensible.

Sill, we would argue the potential of a decentralised, automatable smart contract approach is undeniably high — not only for comparatively trivial land register registrations, but above all for the creation of an overarching decentralised infrastructure for the real estate industry, which brings all players together and enables completely new forms of cooperation and process and cost optimisations.

Open for data exchange, property management and new identity solutions

Applications and systems such as building or land registry offices can be based on a decentralised land registry infrastructure in order to be able to view each other’s documents and make changes. In addition, real estate management applications could be integrated that obtain their information directly from land registers or building offices — of course with verifiable consent and notarial digital verification of the documents.

A fundamental building block in this approach is self-sovereign identities (SSI) — a still somewhat fledgling process for representing identity and credential information that enables tamper-proof proofing of digital identity and authorisation characteristics. Users equipped with SSI wallets can automatically obtain access to the land registry data concerning them without having to have their authorisations manually verified in advance.

The use of self-sovereign identities for official communication is already being tested at the European and German level, for example in pilot projects by IDUnion or ID Ideal, against the background of the European interoperability standard eSSIF and as a connectable technology to the European eIDAS identity framework, to which the new German digital ID card is also compatible.

Setting the course for token-based real estate trading

A digital land register does not have to limit itself to its function as a digital register, but can be directly linked to trading. By starting to write information about property, owners and buildings on a decentralised public register, we can lay the foundation for later automation, verifiable transactions and even token-based trading of real estate with all its economic implications in the token economy.

The analogue land register established trust through officially authenticated information; a blockchain-based land register achieves this through its technological foundation alone. Beyond that, however, it enables transactions between participants who don’t necessarily even know each other. It has the potential to dramatically simplify extremely sluggish, expensive processes and even make them more secure.

Timothy Becker, Director Technology Innovation

timothy.becker@turbinekreuzberg.com

Turbine Kreuzberg's Tech Innovation Unit identifies emerging technologies at an early stage and evaluates their benefits, as well as finding the right areas to apply them. Together with our clients and partners, we build tangible projects to tackle new technological challenges.

How we can work together?

Find out here.